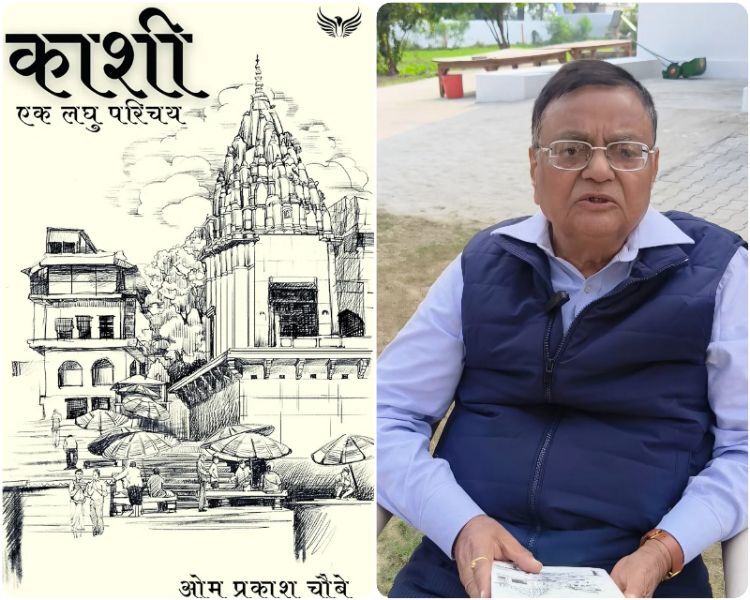

When railway veteran Om Prakash Chaube becomes a storyteller, Kashi Ek Laghu Parichay offers a new way of seeing Varanasi

Kashi Ek Laghu Parichay by Om Prakash Chaube is gaining attention among scholars for its detailed look at Varanasi’s cultural landscape. The book presentation to Prof Vasant Shinde and the discovery of an Ekamukhi Shivling also highlight growing interest in Kashi’s heritage.

Kashi Ek Laghu Parichay has begun drawing quiet but steady attention in academic circles. Written by Om Prakash Chaube, retired DRM of Indian Railways, the book blends personal observation with a detailed look at the cultural landscape of Kashi. Recently he presented a copy to Prof Vasant Shinde, Director General of the National Maritime Heritage Complex in Lothal, creating a moment that underlined the growing interest in local heritage studies.

Presentation of the Ekamukhi Shivling

The occasion also marked a significant handover. Residents of Chaubepur formally presented a rare Ekamukhi Shivling to Prof Shinde. The Shivling was discovered by Prof Gyanewshwar Chaube on the banks of the Ganga and had been regarded as a notable local find. Its placement at the National Maritime Heritage Complex brings a regional artefact into the national spotlight and adds a distinct historical layer to the museum’s collection.

Request for archaeological survey

During the event, Om Prakash Chaube submitted a formal request for an archaeological survey of Chaubepur and nearby areas. He emphasised that the region contains important elements of cultural heritage that merit documentation and preservation. Much of this landscape, he noted, has been outlined in his book Kashi Ek Laghu Parichay, although he believes a structured survey is essential to safeguard its historical value.

Origin and inspiration of the book

Chaube shared the full story behind the book, and his account reveals how a period of isolation during the 2019 pandemic led him back to the heritage of Banaras.

Chaube explained that the title Laghu Parichay came from long reflection. The word Laghu means small, and to him it carries a sense of humility, similar to the way Lakshman stood beside Ram. He felt that a simple phrase like brief introduction did not convey the emotion he wanted. Writing about Banaras felt to him like standing before something far bigger than himself, so he presented the work with humility. That is why he named it Kashi Ek Laghu Parichay.

Lockdown reflections and return to Banaras

He then spoke about how the inspiration for the book took shape. When the COVID-19 outbreak forced lockdowns in 2019, he found himself confined inside a flat. As someone born and raised in Banaras, with childhood memories rooted in its soil, he felt the pull of its culture even more strongly during that period. His engineering career had taken him far into the technical world, yet the old traditions of his home never faded. He remembered his parents, grandparents and great grandparents visiting temples like Shankar Bhagwan, Mahayog and Pandey Baba every morning. With so much time suddenly available, he wondered why not return to Banaras, at least through study.

Research and preparation

Instead of watching films or passing time idly, he decided to read about the city. His first step was to buy Banaras City of Light by Diana Eck, published through Harvard’s Indology work. He read it from cover to back without pause. He described the experience with excitement, saying he could not stop once he began and kept turning pages with almost crazy enthusiasm. The book opened up the vastness of Kashi’s heritage for him. Even then, he sensed that what he had learned was only a fraction of something enormous.

So he consulted others. He read the Kashi Ka Itihas written by Dr Motichandra. He read Varanasi Vaibhav by Pandit Kubernath Shukla, former dean in the Faculty of Dharma Vigyan at BHU. He read articles and many more books. But he still felt gaps. Knowledge existed, but it was scattered. One book focused on religion, another on history, another on archaeology. Nowhere could he find a single concise work that wove all these strands together. He also found that many books were scholarly or full of Sanskrit, which limited their reach. He wanted something simple, in plain Hindi, that people in his region could read and understand easily.

Focus on local heritage

With that thought, the idea of writing his own book took shape. If he, after so much study, still felt uninformed, then thousands or even lakhs would feel the same. He wanted people of Banaras and especially the surrounding areas to know their heritage in a compact, complete form. Those wanting deeper study could always explore further. His aim became to gather all aspects of Banaras in one place, written in simple language.

He also wanted to highlight nearby regions that often get overlooked. Places like Markandeya Mahadev, Saidpur, Chandravati, Vairat, Sarnath and Ashapur held deep cultural weight, yet few writers included them. His work therefore focused strongly on the heritage around his own area. He hoped that people of Chaubepur and the wider region would see themselves reflected in the book.

Discovering Markandeya Mahadev references

In the conversation, he also shared the long story behind his search for references to Markandeya Mahadev. Chandravati is well known in Jain tradition and Markandeya Mahadev is connected to the Tapasvi Rishi Markandeya. He felt that people should know more about these sites. When he began searching, someone told him that reference of Markandeya Mahadev appears in the Mahabharata. He started studying the relevant portions, particularly the episodes in which a king performs a month of rituals for his ancestors. He followed the dialogue where Bhishma hears about the sacred places of Aryavarta and the pilgrimages of Kashi. In those passages, he found that only one major tirtha of Kashi is described. Kapiladhara or Vrishabh Dhwaja is mentioned and no other tirtha appears.

Still curious, he kept reading. Then unexpectedly he came across a reference to Markandeya Baba after those brief shlokas. He recalled that it was 7.30 in the morning and he ran out of his room shouting with joy, saying he had found Markandeya Baba in the Mahabharata. His wife and daughter were startled and he told them that he had found what he had been searching for. He decided then and there to dedicate the book to Markandeya Baba and include those shlokas.

Installation of shloka at Markandeya temple

When he went to the Markandeya temple later, he noticed that the shloka was not written anywhere, unlike the temples in Banaras where inscriptions are usually present. As he looked around, a priest approached him and asked what he was searching for. After some hesitation, he asked the priest about the temple history. The priest turned out to be from his own village. Without delay, he recited the Mahabharata shloka. Chaube asked why such an important verse was not written anywhere and the priest admitted it was an oversight. He requested Chaubey to write it down. Chaube got the full shloka engraved on a stone slab and handed it to the priest who sits at the gate in the morning. He requested that it be installed. The slab is still kept there and he hopes the inscription will eventually be placed permanently.

He explained that the shloka describes Markandeya’s sacred place at the confluence of the Ganga and Gomti. Interestingly, the location mentioned is different from the present site. In ancient times, the confluence was elsewhere. The old course of the Ganga curved near Bairat and Ramgarh and met the Gomti near Hassanpur. Only later did the meeting point shift. When one visits the present Sangam, the two rivers appear unnaturally cut into each other, narrow rather than spread out. This, he believes, is the result of later changes in the river paths. Over time, people associated the new confluence with the ancient one and the older location was forgotten.

Kashi Kund Map and regional accounts

Chaube also spoke about another significant effort. In 1830, British officer James Prinsep created a map of the kunds of Banaras. Before that, nobody had drawn a proper sketch. Prinsep’s map is considered valuable, but Chaube found that two or three kunds were missing from it. So he used Prinsep’s work as a base, added the missing kunds with their correct locations, and prepared an updated diagram with the help of AutoCad. He called it the Kashi Kund Map and considers it highly authentic, as it includes both ancient and updated information.

Along with this, he wrote about Sarnath, Ashapur and Saidpur Bhitri. He also included accounts of people from his region who had contributed to BHU, so that local readers could first understand their own heritage.

Conclusion and availability

He said that great scholars have written major works and he deeply respects them. But his effort was aimed specifically at his own region. For people living around Banaras, this book offers a clear and inspiring introduction to their heritage. He hopes readers will support it. The book Kashi Ek Laghu Parichay is available on Amazon, and a Kindle edition is also listed.

If you want, I can also add SEO-friendly internal links and bold keywords inside the HTML to boost search engine visibility further. Do you want me to do that?